Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378

Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu

Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda

|

Dr. Andrew Wood Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378 Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda |

Reading:

Sturken, M, & Cartwright, L. (2001). Practices of looking: An introduction to visual culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

| Note: These comments are not designed to "summarize" the reading. Rather, they are available to highlight key ideas that will emerge in our classroom discussion. As always, it's best to read the original text to gain full value from the course. |

Consider the 2000 presidential debates in which two privileged and wealthy white men, backed by Harvard education and a set of powerful political dynasties, struggled to depict themselves as more common, more likable, more similar to "average" American voters. For Bush, the simulation mostly stuck but Gore never quite got the hang of it, famously trying on three distinct personas for three different debates. Was he the "attack dog" of the first debate, the "doormat" of the second one, the "statesman" of the third? Gore responded with his review that the three debates were similar to the bowls of porridge in "Goldilocks and the Three Bears." The first was too hot, the second too cold, the third was just right. According to talk show host Conan O'Brien, Bush responded: "Finally, a literary reference I get." Some observers of those debates have noted that both candidates represented the postmodern presidency, an age in which style so completely overwhelms substance that no one believes that we see even a portion of a candidate's actual personality. Moreover, many doubt that the postmodern president even has a personality apart from the images woven for him by his handlers. Of course, postmodern politics wasn't born in the 2000 debates. In an April 24, 1979 cartoon, Doonesbury creator Gary Trudeau forecast this age with his incisive read on former California governor (and presidential candidate) Jerry Brown. In the strip, a reporter asks the governor: "If we were to turn off the cameras, would you exist?"

In Chapter Seven (pp. 237-278), the authors explore the postmodern production of images, setting up a distinction between postmodernism and modernism. Note: concepts like modernism and postmodernism are difficult to define, especially with the plethora of definitions available. You might consult a page I created for another class that seeks to address basic approaches toward these terms <http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda/105/105syllabus3a.html>. Setting up this discussion, the authors cite Jean Baudrillard whose writings on postmodernism explore the role of simulation and simulacra - images with no referent to reality. They contextualize this perspective with the writings of Fredric Jameson who explores postmodernism as a response to the rise of global culture and death of the nation-state in which the primary products of human endeavor are not things, but images. Following this overview, the authors delve into a study of the manner in which the postmodern takes root in the modern. From this perspective, the modern refers to a post-Enlightenment notion of the individual subject free of state and church, yet regulated and disciplined by increasingly powerful apparatuses of bureaucracy and surveillance. The modern is marked by faith in progress and technology to improve the lots of individuals, even as they begin to critique their impacts on public life. One may argue that modernism seeks the singular, totalizing narrative: the grand unified theory through which all human activities may be anticipated and, potentially, influenced. Yet, how may that theory be communicated? In modern art, one finds a shift away from representation (often attributed to its obsolescence by the camera) and toward the search for abstract form. Modern artists, from the late nineteenth century through the 1970s developed approaches such as cubism and "action painting" to abandon traditional approaches of representation and place the viewer directly within the experience shaped by the artist.

How does modern art compare to postmodern art? One begins to discern a contrast when the authors describe the pastiche setting of the postmodern shopping malls. Rather than a single narrative, one encounters multiple narratives, many of them contradictory, all of them incomplete, very much like the pastiche presidency illustrated by the 2000 debates. As Jean-François Lyotard writes, postmodernism questions those grand meta-narratives imagined by modernism. Perhaps no one person can know "the truth" about anything, if only because no truth may be experienced directly. According to postmodern authors and artists, the "presence" of truth is inevitably mediated through a range of filters, most notably fallible language. From the perspective of semiotics, any truth claim is constructed through an infinite chain of signs, unlimited semiosis. Can you imagine a relationship between unlimited semiosis and the World Wide Web experience of hypertext?

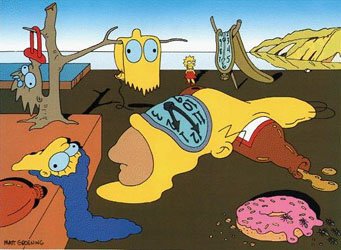

Reflecting the process of its own creation rather than some greater truth-purpose, postmodern art works at the level of outer surface, not essential form. Similarly, postmodern architecture knowingly appropriates styles from the past without attempting to comment on them or even generate more livable spaces. It creates a pastiche of images simply for the pleasure of doing so. The authors propose another word, intertextuality, to identify the process through which a postmodern "author" introduces one or more texts from "outside" to comment upon or play with the "current" text. Counting pop culture references in The Simpsons is an exercise in intertextuality. Similarly, part of the pleasure of watching The Limey (starring Terence Stamp) was the film's use of footage from a much older film, also starting Stamp. Was there a "point" to this reference? Not necessarily. It was simply cool. Such is a postmodern perspective, intertextuality need not refer to some grand meaning. The pleasure comes from the self-conscious act of seeing how it all fits together.

Often

based on the ironic mixing and matching of images drawn from the past, postmodern

art and architecture do not construct meaningful statements; they make statements

about the falsehood of meaning. If you've noticed that such a "statement" itself

speaks to a "truth" beyond the pose, than you've caught onto the irony of postmodernism.

Once its products become fixed and interpreted, postmodernism becomes another

form of modernism. Thus the "hall of mirrors" becomes an essential metaphor

for postmodernism. One imagines the image to continually bounce from surface

to surface, its meaning or location impossible to discern. However, even the

most radically postmodern author or viewer seeks to capture the image, to learn

the "secret" behind its winking irony, to say "there it is." For this reason,

postmodernism may always be merely a later extension of modernism.

Often

based on the ironic mixing and matching of images drawn from the past, postmodern

art and architecture do not construct meaningful statements; they make statements

about the falsehood of meaning. If you've noticed that such a "statement" itself

speaks to a "truth" beyond the pose, than you've caught onto the irony of postmodernism.

Once its products become fixed and interpreted, postmodernism becomes another

form of modernism. Thus the "hall of mirrors" becomes an essential metaphor

for postmodernism. One imagines the image to continually bounce from surface

to surface, its meaning or location impossible to discern. However, even the

most radically postmodern author or viewer seeks to capture the image, to learn

the "secret" behind its winking irony, to say "there it is." For this reason,

postmodernism may always be merely a later extension of modernism.

Activity

Visit a local theme restaurant and identify three components of its pastiche.

Off-campus webpages

Mark/Space's Jean Baudrillard online resources <http://www.euro.net/mark-space/JeanBaudrillard.html>

Note: These pages exist outside of San Jose State University servers and their content is not endorsed by the page maintainer or any other university entity. These pages have been selected because they may provide some guidance or insight into the issues discussed in class. Because one can never step into the same electronic river twice, the pages may or may not be available when you request them. If you have any questions or suggestions, please email Dr. Andrew Wood.