Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378

Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu

Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda

|

Dr. Andrew Wood Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378 Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda |

Reading:

Sturken, M, & Cartwright, L. (2001). Practices of looking: An introduction to visual culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

| Note: These comments are not designed to "summarize" the reading. Rather, they are available to highlight key ideas that will emerge in our classroom discussion. As always, it's best to read the original text to gain full value from the course. |

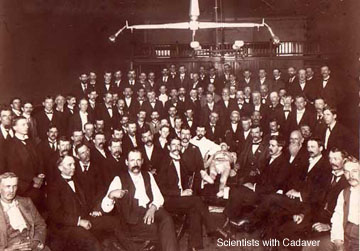

In Chapter Eight (pp. 279-314), the authors state that all visual communication, even supposedly objective imagery from the scientific world, resides within a complex web of social and cultural relationships. This claim demands our attention because we seek "truth" from the world of science, imagining that this realm offers value-free observations of the world "as it is." However, the most apparently objective means to generate visual images, the camera, was frequently used in the nineteenth century scientists to affirm ideologies of race and gender - not to understand the world as it is, but to affirm assumptions that some people believe. The authors propose that the epistemology - how we know what we know - of science becomes shaped by the increasingly visual means through which knowledge is generated and transmitted. In other words, the visual communication of science emerges from a certain discourse, a set of rules and practices for what may be spoken, for what counts as truth.

Initially, the authors explore the use of film images to portray truth, noting the videotape of Rodney King's beating by LA police in 1991. This supposedly neutral depiction of police violence was effectively transformed into a "neutral" portrayal of King's violence simply by pausing the tape and viewing images out of chronological context. From a scientific perspective, such analysis is essential. One must focus on portions of the world to gain a clearer perspective on the entire world. Thus questions arise: which portions shall one choose? What form of interpretation shall one adopt?

The authors then turn to a discussion of imagery in medical science, describing the taking of sonograms as an interpretative act based less on medical needs than on cultural expectations, proposing even that the sonogram provides scientific legitimacy to certain attitudes about pregnancy and the personhood of fetuses. These biomedical images conform to Foucault's notion of the clinical gaze that asserts the power of dispassionate observation, often through invasive procedures, over the lived or "felt" experience of health and illness. A contemporary example of this clinical gaze emerges in attempts to "map" the human genome. In many ways, this "deeper gaze" upon the abstracted self makes possible the abolition of practices designed to encounter human beings as individuals. Through the age of computer mapping, individuals become members of groups whose genetic "markers" may be identified and categorized in ways that enable ideologies of difference and naturalized inequity.

The authors conclude the chapter with a discussion of ways in which cultural agents such as advertisers appropriate scientific imagery (such as the "white lab coat") to sell their products. They note, however, that scientists often depend upon popular culture images to communicate and even imagine their efforts. Thus science and culture becomes ever more blurred.