Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378

Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu

Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda

|

Dr. Andrew Wood Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378 Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda |

Introduction

: Course Calendar : Policies

: Readings

Assignments : Check Your Grades : Return

to Frontpage

Reading: Bryson, B. (1999). I’m a stranger here myself: Notes on returning to America after twenty years away. New York: Broadway Books.

Bryson devotes several essays to the changing role of transportation in the United States, with particular emphasis on the impact of the interstate highway system on cultural identity. In "why no one walks," he notes that Americans are increasingly sedentary, preferring to drive even when the distance would accommodate a short walk. Most interestingly, Bryson states that suburban design makes it virtually impossible to walk anywhere: "Go to almost any suburb developed in the last thirty years and you will not find a sidewalk anywhere. Often you won't find a single pedestrian crossing" (p. 103). Assuming that Bryson is correct in his complaint about our car-centric society, what are its qualities?

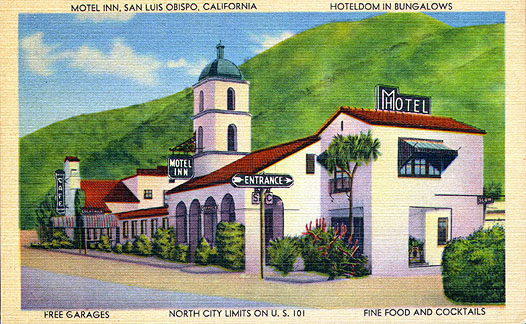

In an essay entitled "highway diversions," Bryson describes this autotopia as being mind-numbingly dull - in contrast to the pre-interstate days when highways were lined with billboards, diners, motels, and other structures, when motorists confronted the ugliness and tackiness of roadside America. Of course, motorists must at some point stop for the night. In his essay, "room service," Bryson describes his love of mom and pop motels - the kinds that have largely been bypassed by the interstate and their accompanying hotel/motel chains.

During the so-called "golden age" of motels, virtually each one was individually owned which all but assured some unique qualities. Sure enough, to compete with dozens of other motels along the various strips entering and exiting a mid-sized town, motel owners drew from a wide range of motifs: space age to reflect nuclear age fascinations with technology, western to tap a cultural reservoir based on the "frontier," cottages that recalled Hansel and Gretel narratives from childhood - and dozens of others.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of roadside America is the blurring of domesticity and public life in the form of drive-in movie theaters. The automobile because an intersection of communal activity, cars lined up in rows and occupants observing the same entertainment, even as "you can smoke and drink beer and smooch extravagantly" (p. 191). More than a celebration of "America's love affair with the car," drive-ins reflect a particularly modern blurring of medium and motoring wherein the scene beyond the window becomes less "real" and, instead, a framed source of entertainment.

Finally, Bryson notes one recent phenomenon, due in large part to the increasing mobility of Americans in the interstate-age: the decline of regional dialects. This decline is not necessarily permanent, however. Describing the changing dialect of Ocracoke Islanders, Bryson cites research on middle-aged islanders whose dialects had become more pronounced than those of their elders, presumably as a subtle form of cultural resistance to the waves of tourism that had seemingly overtaken the island. Even in the age of mobility, distinct identities may yet flourish.