Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378

Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu

Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda

|

Dr. Andrew Wood Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378 Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda |

Introduction

: Course Calendar : Policies

: Readings

Assignments : Check Your Grades : Return

to Frontpage

Study guide: Focus on (1) two eighteenth century Swedish writers who experienced the same landscape in different ways, (2) the first theme park, (3) the eighteenth century icon of the sublime, (4) the first national park in America, (5) landscape patriotism.

An initial question that animates this class is fairly simple: is tourism as experienced in contemporary life radically different than in earlier days? In his book, On Holiday (pp. 13-60; 64-71), Orvar Löfgren describes the work of some sociologists, most notably Gerhald Schulze, whose concept of Erlebnisgesellschaft (er-leb-nis-ge-SHELL-shaft) posits that contemporary society is obsessed with the collection of "experiences" that are collected, compared, and commodified. In contrast, Löfgren claims that, for at least the past two centuries, tourism has represented the ritualized search for varied sensual experiences. How we experience tourism isn't so new to Löfgren.

The eighteenth century prism through which tourists experienced their environment was the picturesque, "a certain way of selecting, framing, and representing views" (p. 19). The picturesque represented a search for particular vantage-points, specific mixtures of human-made and natural components, precise shades and colors. In fact, the earliest theme parks may be said to have been English pleasure gardens that sought to balance between geometrical "garden" and naturalized "wilderness." In his 1731 Epistle to burlington Alexander Pope writes:

Let not each beauty ev'ry where by spy'd

Where half the skill is decently to hide.

He gains all points, who pleasantly confounds

Surprises, varies, and conceals the Bounds.

Balanced between wild and the tame, English pleasure gardens were fashioned to contain texts to be conjured and synthesized by its visitors: "tiny landscape details had far-reaching literary, historical, and aesthetic connotations, stimulating the mind and creating a massive symbolic space out of this little park" (p. 22). The desire to craft these environments even included the attempted inclusion of real "hermits" who would display pre-modern solitude for passers-by. Given the class distinctions enjoyed by these travelers, it's not too difficult to spy an apparently inviolable divide between ordinary workers who toiled on the land and aesthetically trained tourists who, alone, could appreciate its picturesque qualities.

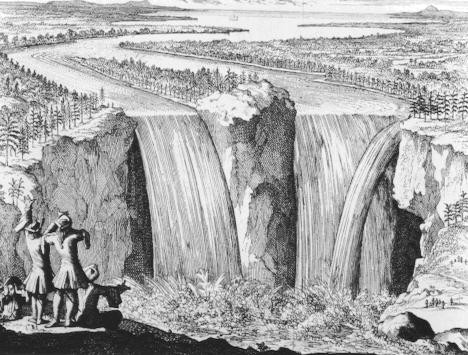

It didn't take long for this search for the picturesque to become somewhat tiresome. How many "perfect" scenes can one experience before they lose their uniqueness? Quoting Denis Diderot, Löfgren describes the "cult of the sublime" as the search for even more heightened sensation: "all that surprises the soul, all that creates a sense of fear" (p. 27). Perhaps the eighteenth century example of sublime was the Niagara Falls. Of course, its sublime nature diminished somewhat as the Falls became more accessible to travelers, thanks to the improvements in steam transportation. In fact, before long, Niagara become an overdeveloped training ground for uncultured tourists seeking the sublime experience they'd read about, frustrating the "real" tourists who claimed that they, alone, could appreciate its beauty. By the nineteenth, U.S. tourists discovered even more opportunities to experience the sublime as entrepreneurs rushed to capitalize on a new desire for Americans to compete with Europeans for the possession of national treasures. Heading west, further into the "wilderness" (as imagined by white settlers), tourists sought ever more spectacular scenes. This so-called nationalizing of the sublime created an intriguing relationship between transportation, media, and nature. As trains and automobiles made it possible for more and more tourists to venture further away from the east coast, and as nineteenth century cameras made it possible to portray the sublime in ever more sophisticated ways, natural sites became significant, "real," only once they were rhetorically framed - ultimately, as national parks.

Löfgren's chapter, "On the Move," explores the framing of the picturesque into aesthetically pleasing panoramas whose experiences became increasingly shaped by the mode of transport used to travel through them. At once, natural scenes competed with artificial panoramas constructed to expand human perception beyond its natural limits. The "view" could only be appreciated from a certain vantage-point, enacted through the building of sight-seeing towers. Artificial panoramas, such as cycloramas, served to further optimize human perception by telescoping time as well as space: "The panoramic gaze was part of a new technique of vision, which underlined the observer's detachment from the landscape: looking in, from an outside position. A sweeping glance set the landscape in motion in front of you, at a pace you controlled" (p. 45). Of course, the artificiality enacted through new modes of transportation inspired a return to a more traditional way to experience the landscape, walking. For many male tourists, walking provided an opportunity to differentiate from supposedly effeminate modes of travel. The "true" wilderness became feminized, verdant, to be tamed. The metaphoric construction of gender in the form of machine and landscape emerges again as an underlying theme of tourist literature.

The popularization of the automobile provided a compromise between the oppressive collectivism of the steamboat or train and the occasionally excessive rigors of walking. The car also reaffirmed the role of speed in the construction of the tourist experience. With the addition of car radios and cruise control, the automobile became a paradoxical locale - moving through the land and yet unaffected by the landscape: "The fast lane of the freeway thus turned into a space for meditation and roving minds, coupled with new types of visions made possible by General Motors' introduction of the panorama window" (p. 60). Further along in this course, we will explore in more detail the impact of automobile travel on perception, space, and culture.

Activity

Consider the discussion of how early parks contained texts and fragments meant to stimulate the mind, to create symbolic space. Visit a "themed" restaurant nearby and develop a one-page summary of its use of fragments to evoke a certain kind of experience. For your Show and Tell activity, explore what social knowledge or cultural literacy must its patrons share to make sense of this place?