Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378

Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu

Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda

|

Dr. Andrew Wood Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378 Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda |

Introduction

: Course Calendar : Policies

: Readings

Assignments : Check Your Grades : Return

to Frontpage

Reading: Picard, M. (1996). Bali: Cultural tourism and touristic culture (D. Darling, Trans.). Singapore: Archipelago Press.

Bali, an island located in the Indonesian archipelago, demands our attention because of the manner in which its inhabitants have struggled to integrate colonial and touristic practices with native ones. In his chapter, "Balinese dance as a tourist attraction" (pp. 134-163), Michael Picard describes the contest between cultural tourism - "tourism that nurtures the resources it exploits" (p. 121) - and touristic culture - "a culture that has been able to adapt itself to tourists and their demands" (p. 165) by exploring certain forms of Balinese dance as both an artificial creation for the sake of tourists and a significant ritual affirming traditional culture on the island.

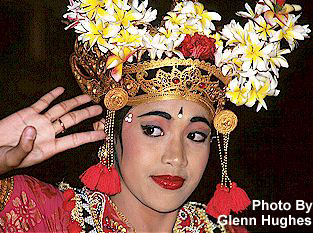

While traditional Balinese dance reflects a host of religious and cultural ties, visitors to Bali are more likely to experience Legong dance, a series of short exhibitions created for tourists that have little to do with Balinese traditions: "For anyone who is even a little familiar with dance and theater in Bali, it is obvious that such performances are far removed from the tastes of the Balinese public" (p. 142). Intriguingly, some dances - originally performed to welcome deities - have been refashioned as more generic "welcome, tourist" dances, such as the Panyembrama. Then, as new generations of dancers learned that style, the tourist dance has begun to supplant the original within Balinese temples.

Another impact of tourists upon Balinese dance is the introduction of interpreters who explain the movements to audiences, rendering the dancers as mere mimes of a prepackaged script - illustrated by the Ramayana Ballet. This is significant, Picard notes, because some forms of Balinese dance enables a kinetic dialogue between cultural traditions and local/contemporary problems. Once refashioned into a generic and linear script, the dances lose their meanings as a site of Balinese dialogue.

Similarly, exorcistic dances find themselves westernized - such as the Barong and Kris dance that has been transformed from an affirmation of equilibrium between balanced powers into battle of "good" and "evil," even though, "to express the fight between the Barong and Rangda in terms of good and evil is to miss the point" (p. 155). Or, they are simply detached from their original purpose - illustrated by the Monkey Dance, the Angel Dance, and the Fire Dance - performed without their original purposes as a means to stave off illness. A result is the blurring of theater and ritual.

Responding to these issues, Balinese leaders have sought to differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate displays of their dances. Ironically, they have been forced to employ the language of their colonizers to make this distinction between the so-called sacred and profane, concepts not typically viewed as a dichotomy to the Balinese: "Not only are they called upon to slice into the living flesh of their culture, to perform a new, unknown incision . . . they are obliged to think in a borrowed terminology that visibly makes no sense to them" (p. 153). Beyond this semantic difficulty, a larger question remains: Will the Balinese strengthen their cultural foundations, or will their significant symbols become reduced even further as mere objects of global consumer desire?

Activity

Identify a cultural tradition in your personal background that risks becoming an object of cultural tourism. For your Show and Tell activity , describe this tradition and the ways in which outsiders have adopted it for unintended uses. What are some tactics employed by members of your culture to retain the original intent of the tradition?