|

Autocamping

and Tourist Homes

In the early part of the twentieth century, there were few of the amenities available to today's interstate traveller. West of the Mississippi, camping was the most common alternative to expensive hotels. Indeed, for motorists who didn't wish to traipse across stuffy lobbies in road-worn clothing, the convenience and anonymity of a farmer's field or lake shore was plenty inviting. In her book, A Long Way from Boston, Beth O'Shea recalls her visit to one of these camps.

"Is this a tourist camp?" I asked, looking around with interest. We had heard about them, but had expected something more elaborate."Sure, it's a tourist camp," he told us. "Anythin's a tourist camp what has water and no no-trespass signs. All the towns has got 'em now. They figure they give you a place where you can pitch your tent and you'll buy food and stuff at their stores. You gals want I should give you a hand with your tent?"

They were both surprised when they learned we hadn't one. They'd run into a lot of boys traveling light like that, they said, but we were the first girls. "But you'll make out all right," Maw assured us. "They say it's real comfortable sleeping' on the ground once you git the trick of it. Me, I like a cot myself, but I'm not so young as I used to be."She and Paw were bound for California too, if the flivver held out. All their lives they'd wanted to see America and now they were seeing it.

At first, towns and villages welcomed auto tourists and their vacation cash. However, it didn't take long for locals to complain about the mess, the commotion, and even the loose morals of travelling folks from out of town. The postcard that refers to "tin can tourists," recalls families who travelled "with one shirt and a $20 bill -- and they didn't change either." Along with the illustration, you can read the accompanying poem by Ruth Raymond.

| Neith the

spreading oak and pine tree tall "A tin can tourist" in the Fall Puts up his tent and plans to stay In Florida till blooming May, And soon another tourist comes, they meet and greet like old time chums, They tell new jokes and make new plans And mess from out of the same tin cans. |

Then other

tourists come along, The camp force now is growing strong Cars from the North, the East, the West, Bring weary tourists seeking rest, All happy in this flower glade Beneath the broad oaks welcome shade they're singing songs and making plans And pile up the empty cans |

And ere the

blooming May comes round they'll buy a piece of fertile ground And mark it off in streets and squares And every tourist take some shares, For they will build a city here When they come back another year Just as the "tin can tourist" plans When he piles up the empty cans. |

In

the first three decades of this century, America cemented its love affair

with the automobile. Indeed, any discussion of roadside architecture would

appear empty without a recollection of how important cars were to their owners.

By necessity, the relationship was an intimate one. Intrepid drivers who set

across the continent on roads such as the Lincoln Highway learned to diagnose

every wheeze, every rumble of their machines; there were few mechanics between

the larger cities. This poem by King A. Woodburn illustrates the attachment

that followed, even for a "flivver" on its last gallon.

In

the first three decades of this century, America cemented its love affair

with the automobile. Indeed, any discussion of roadside architecture would

appear empty without a recollection of how important cars were to their owners.

By necessity, the relationship was an intimate one. Intrepid drivers who set

across the continent on roads such as the Lincoln Highway learned to diagnose

every wheeze, every rumble of their machines; there were few mechanics between

the larger cities. This poem by King A. Woodburn illustrates the attachment

that followed, even for a "flivver" on its last gallon.

| Once she was

straight And full of pep, Had a fast gait And kept her step. |

My eyes they

fill When I'm tempted to part, Because she still Holds a place in my heart. |

| Now she is

faded And beginning to wrinkle, Her eyes look jaded And refuse to twinkle. |

She carried

me to hunt, She carried me to marry, Without a single grunt Or suggestion to tarry. |

| Her time is

not long 'Cause her lungs are weak, Her voice once strong Is reduced to a squeak. |

Along the

countryside Or down by the river I've enjoyed every ride In that dear old "flivver." |

Back

east, tourist homes provided another alternative

to hotels. If you look around in dusty attics or antique shops, you can still

find cardboard signs that advertise "Rooms for Tourists." The Tarry-A-While

tourist home in Ocean City, Maryland, advertised, "Rooms, Running Water,

Bathing From Rooms. Apartments, Modern Conveniences. Special rates April,

May, June and after Labor Day." Because tourist homes were frequently

located in town, they differ somewhat from the contemporary vision of a motel

-- found on the highway, away from the city center. However, each home was

as unique as their owners. As such, they contributed to a central tradition

of motel Americana: "Mom and Pop" ownership.

Back

east, tourist homes provided another alternative

to hotels. If you look around in dusty attics or antique shops, you can still

find cardboard signs that advertise "Rooms for Tourists." The Tarry-A-While

tourist home in Ocean City, Maryland, advertised, "Rooms, Running Water,

Bathing From Rooms. Apartments, Modern Conveniences. Special rates April,

May, June and after Labor Day." Because tourist homes were frequently

located in town, they differ somewhat from the contemporary vision of a motel

-- found on the highway, away from the city center. However, each home was

as unique as their owners. As such, they contributed to a central tradition

of motel Americana: "Mom and Pop" ownership.

Cabin Camps and Cottage Courts

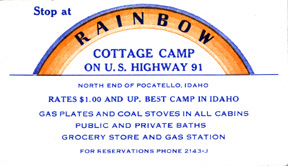

As

the Depression wore on, it became profitable to offer more amenities than

were available in the campsite. Farmers and other business-folks would contract

with an oil company, put up a gas pump, and throw up a few shacks. Some were

pre-fab; others were handmade -- rickety, but original. In their book, The

Motel in America, Jakle, Sculle, and Rogers illustrate the typical visit:

As

the Depression wore on, it became profitable to offer more amenities than

were available in the campsite. Farmers and other business-folks would contract

with an oil company, put up a gas pump, and throw up a few shacks. Some were

pre-fab; others were handmade -- rickety, but original. In their book, The

Motel in America, Jakle, Sculle, and Rogers illustrate the typical visit:

At the U-Smile Cabin Camp . . . arriving guests signed the registry and then paid their money. A cabin without a mattress rented for one dollar; a mattress for two people cost an extra twenty-five cents, and blankets, sheets, and pillows another fifty cents. The manager rode the running boards to show guests to their cabins. Each guest was given a bucket of water from an outside hydrant, along with a scuttle of firewood in the winter.

In a series of short stories called Here on Old Route 7, Joan Connor depicts a day and a life for her protagonist, Anna -- the wife of a cabin camp owner:

When the guests arrived, she registered their names in neat ledgers. She issued keys and made change for the pop machine. She made up the beds of the cabins with hospital corners, emptied the wastebaskets, swept the porch floors. She watched the guests come, sticky and tired, children whining. She watched them go in a rustle of roadmaps and luggage checks, anxious to be on the road. Go and come. Come and go. She and Paulie wanted children, but their children did not come.

Cottage courts (also known as tourist courts) emerged to add some class to these otherwise dingy collections. They were standardized along a common motif and frequently organized around a public lawn. The manager's office and sign began to take more ostentatious forms. The English Village East in White Mountains, New Hampshire, advertised: "Modern and homelike, these bungalows accommodate thousands of tourists who visit this beauty spot in Franconia Notch."

Unlike

downtown hotels, courts were designed to be automobile friendly. You could

park next to your individual room, or under a carport. Along with filling

stations, restaurants and cafes began to appear at these roadside havens.

The Sanders Court in Corbin, Kentucky,

advertised "complete accommodations with tile baths, (abundance of hot

water), carpeted floors, 'Perfect Sleeper' beds, air conditioned, steam heated,

radio in every room, open all year, serving excellent food." Today, you

can visit the KFC in Corbin on the site where the Harland Sanders phenomenon

began, but you'll only find the Sanders Court & Cafe in linen postcards

and the memories of travellers.

Unlike

downtown hotels, courts were designed to be automobile friendly. You could

park next to your individual room, or under a carport. Along with filling

stations, restaurants and cafes began to appear at these roadside havens.

The Sanders Court in Corbin, Kentucky,

advertised "complete accommodations with tile baths, (abundance of hot

water), carpeted floors, 'Perfect Sleeper' beds, air conditioned, steam heated,

radio in every room, open all year, serving excellent food." Today, you

can visit the KFC in Corbin on the site where the Harland Sanders phenomenon

began, but you'll only find the Sanders Court & Cafe in linen postcards

and the memories of travellers.

Motor Courts, Inns, and Highway Hotels

During the thirties and forties, individual owners dominated the roadside haven trade -- with the exception of Lee Torrance and his fledgling Alamo Courts chain. For a time, "courtiers" offered a glimpse of the American Dream: home and business ownership on the same site. The second world war brought rationing on everything related to tourism. Tires, gasoline, and most of all -- leisure time -- were at a premium. However, as troops crossed the country on orders to head overseas, they caught visions of America and planned to see it again with their families. Dwight D. Eisenhower, frustrated by the difficulty of moving tanks across the country, caught a vision of how they would get there. Rumbling along battered one and two-lane roads, he imagined an explosion of efficiency that would follow post-war remodeling of our nation's highway system after the German autobahn plan. But the interstates that would follow were a decade away. Until then, families took to whatever highways were available.

Nat King Cole helped make Route 66 the most popular choice for many cross country adverturers. At night, they found motor courts -- no longer isolated cottages, but fully integrated buildings under a single roof -- lit by neon, designed with flair, and eventually referred to as "motels." While the rooms were plain and functional, the facades took advantage of regional styles (and, occasionally, stereotypes). Owners employed stucco, adobe, stone, brick, whatever was handy, to attract guests.

While

families learned to breeze through these rest-stops that multiplied along

the highways of postwar America, many of the owners settled in for a life's

work. But, soon, those plans were demolished as limited access interstates

began to snake across the nation in the fifties and sixties. Before long,

small-time motor courts were rendered obsolete by chains like Holiday

Inn that began to blur the distinction between motels and hotels. Single

story structures gave way to double and triple deckers. The thrill of discovering

the unique look and feel of a roadside motel was replaced by assurances of

sameness by hosts "from coast to coast," despite some notable exceptions

such as South Carolina's South of

the Border.

While

families learned to breeze through these rest-stops that multiplied along

the highways of postwar America, many of the owners settled in for a life's

work. But, soon, those plans were demolished as limited access interstates

began to snake across the nation in the fifties and sixties. Before long,

small-time motor courts were rendered obsolete by chains like Holiday

Inn that began to blur the distinction between motels and hotels. Single

story structures gave way to double and triple deckers. The thrill of discovering

the unique look and feel of a roadside motel was replaced by assurances of

sameness by hosts "from coast to coast," despite some notable exceptions

such as South Carolina's South of

the Border.

Now, as the interstate system is largely completed, few people go out of their way to find roadside motels. Fewer still remember the traditions of autocamps and tourist courts. However, a growing number of preservation societies and intrepid cultural explorers have begun to hit the exits and travel the highways again -- in search of that one singular experience, just around the bend.