|

In

many ways, Holiday Inn may be called the Wal-Mart of the hospitality world.

In its heyday, Holiday Inn promised low prices, consistent quality, and convenient

locations to a generation of Americans heading out for the highway. And, like

Wal-Mart, the arrival of a bright shiny new Holiday Inn often spelled doom

for the older motels. Free ice, clean pools, kid-friendly pricing, and aggressive

marketing proved an attractive lure for business and leisure travelers.

In

many ways, Holiday Inn may be called the Wal-Mart of the hospitality world.

In its heyday, Holiday Inn promised low prices, consistent quality, and convenient

locations to a generation of Americans heading out for the highway. And, like

Wal-Mart, the arrival of a bright shiny new Holiday Inn often spelled doom

for the older motels. Free ice, clean pools, kid-friendly pricing, and aggressive

marketing proved an attractive lure for business and leisure travelers.

It may appear strange that I as a student and advocate of an older style of roadside architecture would commemorate Holiday Inn. But as the contemporary chain becomes yet another financial holding in a vast conglomerate, I can't help but recall a distant time when the Holiday Inn - with its glowing, garish "great sign" - offered something unique to the highway vernacular.

This site, a subsection of Motel Americana, celebrates the history of Holiday Inn through a collection of postcards and other memorabilia. To save downloading time, I've chosen to place thumbnails of the various images in this essay. Click the button to enjoy the full-size view. Use your browser's BACK button to return to this page. As always, if you have any questions, comments, or suggestions, feel free to email me.

|

|

Holiday Inn began as the vision of Kemmons Wilson (1913-2003) in 1952 and a roadtrip gone bad. Driving to Washington D.C. on a family vacation, Wilson grew frustrated at the lack of quality he found in roadside motels. Dingy courts and dusty motor hotels may have been satisfactory when Americans first set out on the road but Wilson was sure that the interstate-age would call for new kinds of amenities: air conditioning, restaurants, in-room telephones, and - most of all - standardization. Within a year, Wilson commissioned blueprints from his hand-drawn diagrams. The designer, Eddie Bluestein, wrote "Holiday Inn" across the bottom of the plans after seeing a Bing Crosby film. The name stuck. The first Inn, built on Summer Avenue in Memphis, Tennessee, was so successful that Wilson followed up with identical ones on three other roads leading into Memphis.

Recalling

an interview with Wilson for his book The Fifties, David Halberstam

states: Wilson "vows to his wife, 'I'm going to go in business and build

a chain of 400 hotels.' She says, 'You're just crazy.' He does it." Part

of Wilson's success may be attributed to his work ethic. He was known for

his advice: "Only work half a day. It doesn't matter which half you work

-- the first 12 hours or the second 12 hours." By 1972, Wilson was featured

on the cover of Time Magazine - his

company by that point franchised 1,405 inns in the United States and around

the world. The cover story, dated June 12, 1972, describes Wilson's love of

travel that inspired his hands-on involvement in the development of Holiday

Inn: "For that kind of man, no job in the world could offer more: a chance

to chase daylight round the world, clambering over hills, slogging through

rain forests, stalking through prairie grass in a never-ending hunt for the

perfect motel site" (p. 77+).

Recalling

an interview with Wilson for his book The Fifties, David Halberstam

states: Wilson "vows to his wife, 'I'm going to go in business and build

a chain of 400 hotels.' She says, 'You're just crazy.' He does it." Part

of Wilson's success may be attributed to his work ethic. He was known for

his advice: "Only work half a day. It doesn't matter which half you work

-- the first 12 hours or the second 12 hours." By 1972, Wilson was featured

on the cover of Time Magazine - his

company by that point franchised 1,405 inns in the United States and around

the world. The cover story, dated June 12, 1972, describes Wilson's love of

travel that inspired his hands-on involvement in the development of Holiday

Inn: "For that kind of man, no job in the world could offer more: a chance

to chase daylight round the world, clambering over hills, slogging through

rain forests, stalking through prairie grass in a never-ending hunt for the

perfect motel site" (p. 77+).

By the 1970s, Wilson's 300,000 beds outdistanced his nearest competitor in the same market more than three-fold. Companies like Quality Inn, Howard Johnsons, and Ramada Inn found that keeping up with Holiday Inn required matching the company step by step. The results are apparent even today with each room in every motel looking pretty much the same as any other room.

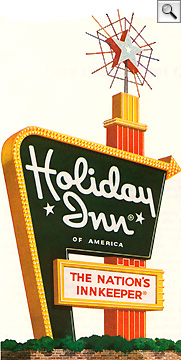

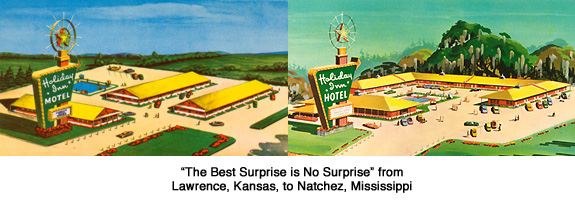

As the chain evolved, it tried its hand at various marketing gimmicks including the oddly conceived John Holiday (right). The evolution of the Holiday Inn may also be studied in its changing slogans. During the 1960s "The Nation's Innkeeper" and "Your Host from Coast to Coast," became "The World's Inn Keeper." In 1975 corporate execs choose "the best surprise is no surprise" as their slogan, promising that a night in one Holiday Inn was like a night in any.

Holiday Inns boasted air-conditioned rooms, restaurants, meeting rooms, pools, television, direct dial telephone service, piped music and radio, wall to wall carpeting, cocktail lounges, and the Holidex - the computerized reservation system that put many Mom and Pop outfits out of business. Millions of road weary business travelers and harried families learned to organize their trips around the ritual of Holidex reservations, knowing that the same room, food, and night-lit pool awaited them down the road.

|

|

By 1980, corporate suits edged Wilson out of his post as Chairman and signaled their plans to alter the image of Holiday Inn. In 1982, Holiday Inn replaced its 43 foot "great sign" with its more subdued cousin of backlit plastic. Recently, they have revived the motif somewhat with the "Relax, it's Holiday Inn" campaign, and there's even been talk about a "modernized" great sign in a small number of prototype properties. But the gorgeously tacky neon marquee can never return for real. In Home Away from Home: Motels in America, John Margolies explains why: "The new expression of a chain hostelry is a sparse but direct graphic that is clearly discernible to those passing by at a high rate of speed on an interstate, and an array of national advertising tied into an 800 number for nearly instantaneous national and international booking and reservations" (pp. 116-117). Today, it is virtually impossible to find a Great Sign (as opposed to clever imitations such as those found in Clarksville, Tennessee, Deland, Florida, and East St. Louis, Illinois). The only one discovered by authors of this page remains in Mt. Airy, North Carolina - repainted as another motel. Please send us an email if you know of others.

In

1990, Holiday Inn ceased to be an American pop culture phenomenon and became

yet another blue chip in an international conglomerate (as of 2004, Intercontinental

Hotels Group). Even so, the impact of Holiday Inn on the roadside and its

travelers cannot be underestimated. In The Motel in America, Jakle,

Sculle, and Rogers (1996) write: Holiday Inn "brought a new, modern look

to the commercial landscape. Whereas many motels

in the late 1950s and early 1960s were low-slung, neon-clad affairs stretched

along the roadside, new Holiday Inns were glass-bright two-story structures

poised by Interstate highway interchanges. The focus of the facility was inward,

toward a public yet private recreational courtyard. And unlike many of the

motels of that era, the Roadside Holiday Inn was built to last" (p. 284).

While authors of Motel Americana

rarely find themselves stopped at Holiday Inn for the night, we cannot help

but agree that for good and ill, this chain permanently reshaped the motel

experience.

In

1990, Holiday Inn ceased to be an American pop culture phenomenon and became

yet another blue chip in an international conglomerate (as of 2004, Intercontinental

Hotels Group). Even so, the impact of Holiday Inn on the roadside and its

travelers cannot be underestimated. In The Motel in America, Jakle,

Sculle, and Rogers (1996) write: Holiday Inn "brought a new, modern look

to the commercial landscape. Whereas many motels

in the late 1950s and early 1960s were low-slung, neon-clad affairs stretched

along the roadside, new Holiday Inns were glass-bright two-story structures

poised by Interstate highway interchanges. The focus of the facility was inward,

toward a public yet private recreational courtyard. And unlike many of the

motels of that era, the Roadside Holiday Inn was built to last" (p. 284).

While authors of Motel Americana

rarely find themselves stopped at Holiday Inn for the night, we cannot help

but agree that for good and ill, this chain permanently reshaped the motel

experience.

Related Websites

Associated Press, "Father of modern hotel dead at 90", CNN <http://www.cnn.com/2003/US/02/13/obit.wilson.ap/>

Laura Bly, "Come Inn off the Highway", USA Today <http://www.usatoday.com/travel/destinations/road/2003-10-10-holiday-inn_x.htm>

Sarah Wernan Buttenwieser, "Your formative year at the Holiday Inn", CrossConnect <http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/xconnect/v6/i2/t/buttenwieser1.html>

Wayne Curtis, "No room at the Inn", The Atlantic <http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/2001/11/curtis.htm>

Andrew Nelson, "The Holiday Inn Sign", Salon <http://www.salon.com/ent/masterpiece/2002/04/29/holiday_inn/>

Note: "Holiday Inn," "Wal-Mart," and "the Great Sign," are registered trademarks.