The ruin as memorial - the memorial as ruin

Arnold-de Simine, S. (2015). The ruin as memorial - the memorial as ruin. Performance Research, 20(3), 94-102.

Silke Arnold-De Simine begins her essay by comparing monuments to

memorials. Monuments, she argues, represent a rhetoric of permanence;

they signify the endurance of their builders. Memorials, in contrast,

index the inevitability of change; they remind their beholders of

"memento mori," confirmation that the desire to hold onto life is

vanity. This is a rhetorical move, one that argues for the destruction

of old orders, yes, but also invokes the creation of new ones.

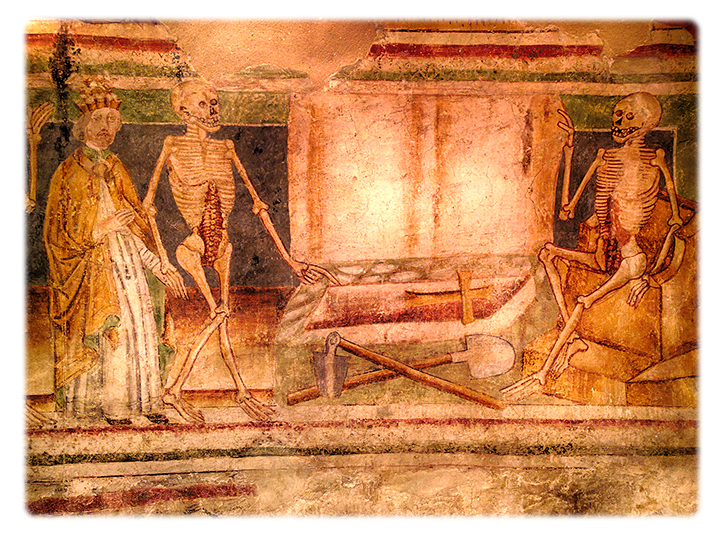

Johannes

de Castua's (1490) Danse Macabre, Holy Trinity Church, Hrastovlje,

Slovenia -

a reminder that all people, no matter their station in life,

are mortal [photograph by Andrew Wood]

While our class will investigate other sorts of ruins, we begin with

her essay because of the provocative questions she seeks to surface.

Initially she notes poetic efforts (Andreas Gryphius, William Blake,

and Percy Bysshe Shelley) to position ruins as a contrast between

nature and culture, a distinction that may remind you of classroom

conversations concerning the garden and the machine.

From this perspective, culture becomes a machine that works, often

through architecture, to impose a tyranny of meaning upon people.

Nature, through the inevitable process of ruin, humbles those efforts.

[Keep in mind that this distinction between culture and nature will be

complicated by the end of this essay.]

From this perspective, Arnold-De Simine turns her attention to the

effect of ruins upon time. In a world without ruins, we may easily

separate the past from the present; we live in

the here and now, safely insulated from yesterday's reminders of

mortality, free to project ourselves into the future. The presence of

ruins, though, reminds us that all our yesterdays, borrowing from Macbeth,

"have lighted fools / The way to dusty death." Here we see the

tomorrows of yesterday as reminders that all our plans will come to

ruin, just as they always have. Yes, of course, we are reminded once

more of William Gibson's Gernsback Continuum, recognizing his protagonist's preference for ruins over illusory perfection.

Thus Arnold-De Simine proposes, "[r]uins have a utopian, apocalyptic

and nostalgic potential, they are heterotopias of time and space" (p.

95). To illustrate the pleasures of these "competing temporalities,"

the author describes Ostalgia, "nostalgia for the everyday life of the

old communist East" (p. 95). Visiting places such as this, inhabiting

the ruins of those tomorrows imagined by yesterday's authoritarians, we

learn to "question the neat linear temporality of historical progress"

(p. 95). Such inquiry, she adds, is not solely the province of poets

and professors; it is increasingly a touristic pursuit.

Szimpla Kert (2019) - "Ruin bar" in Budapest, Hungary [photograph by Andrew Wood]

At this point, Arnold-De Simine shifts to the analysis of two memorial

sites whose evocation of past traumas raise ethical questions about the

odd pleasures of Dark Tourism. She begins with Budapest's Memorial to

the Victims of the German Occupation, a site created to evoke a sense

of ruin - illustrated by its inclusion of an intentionally broken

column - even though it was erected in 2014. Analyzing this site, the

author describes efforts by memorial designers to produce a

trauma-narrative that defines Hungary as the victim of German

aggression while ignoring the nation's wartime complicity with the Nazi

regime and failing to account for human victims of that alliance, most

notably Hungary's Jewish and Roma populations. In this way, she

demonstrates one dimension of the rhetoric of ruins: the deployment of

an artificial past that silences the ghosts of forgotten yesterdays.

The author then turns toward an analysis of Argentina's ESMA

Complex, a site where political activists were subjected to

imprisonment, torture, and death during that nation's 1976-1983

military dictatorship. Once more we encounter a site of trauma, but not

an artificially constructed one. This place stood, containing real

horror. Yet how should the victims of that time be memorialized? Some

activists argued that the building should remain as it was, but that

its interior should include a Museum of Memory with audiovisual

installations to educate visitors about the miseries suffered by

Argentina's political prisoners. Others disagreed with that strategy,

fearing that transforming the building into a tourist site would not

summon the ghosts of the past but would rather mute their voices under

the din of sanitized media production. Part of their concern with the

museum that did emerge was that the transformation of suffering into

mediated memory would "suggest a form of closure" (p. 99) when, in the

case of the disappeared prisoners, no such closure could be offered.

Thus Arnold-De Simine confirms that museums, no matter how well

intended in their designs, cannot affect people in the same manner as

ruins: "[T]he ruin resists any interpretative closure and creates a

spatial-temporal situation in which the past cannot be contained, its

unsettling excess leaking into the present as affective disturbance"

(p. 99). Again, she harkens to the imagery of ghosts who haunt us, not

with their easily fixed memory but through their abilities to drag the

past into the present.

Arnold-de Simine concludes her essay with a discussion

of the ethical implications of ruins that contribute further to our

rhetorical perspective. Ruins, she says, obscure our efforts to fix any

sort of meaning. They blur domains of presence and absence, today and

yesterday. As such, ruins call into question the potential of agency,

of authorship, and potentially of responsibility. To illustrate this

challenge, the author associates the sinking of the Titanic with

the imminence of climate change. These "modern" ruins do not represent

a divide between nature and culture but rather a collapse between the

two that marks our present Anthropocene Age. As such, the rhetoric of

ruins risks the creation of a sense of inevitability, that we cannot

avoid the wreck of tomorrow any more than we can exorcise the ghosts of

yesterday - that is unless we recognize that our memorials of past and

future ultimately, always, speak to our circumstances in the here and

now, summoning us to act.