Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378

Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu

Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda

|

Dr. Andrew Wood Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378 Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda |

Reading:

Sorkin, M. (1999). See you in Disneyland. In M. Sorkin's (Ed.), Variations on a theme park: The new American city and the end of public space. New York: Hill and Wang.

| Note: These comments are not designed to "summarize" the reading. Rather, they are available to highlight key ideas that will emerge in our classroom discussion. As always, it's best to read the original text to gain full value from the course. |

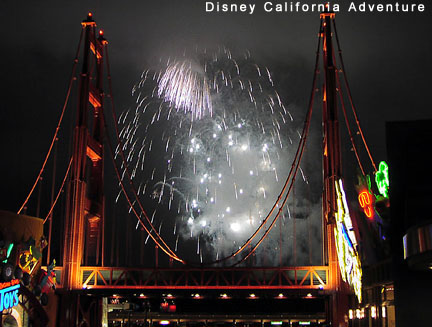

Consider Disney's California Adventure: a theme park which promises a streamlined experience of California, a place where Californians may visit that is both familiar and exotic. In many ways, DCA epitomizes any of the arguments found in the Sorkin piece, itself a nearly perfect summary of many ideas addressed in this class. From Sorkin's perspective, DCA and its older brother, Disneyland, represents a world created to evoke an ideology through the mass-production of fantasy and iconic images. At one point, Sorkin labels Disney the "alphapoint of hyperreality" (p. 206): a quintessentially postmodern locale.

Providing a paradoxical departure from our course's exploration of architecture, Disneyland introduces "antigeographical space" (p. 208). In other words, its location in Anaheim - or Orlando, or Tokyo, or wherever - is less important than its location in a cultural space of signs and symbols. Moreover, this space is less a flat plane of coherent narrative than a postmodern pastiche, a "channel-turning mingle of history and fantasy, reality and simulation . . . a way of encountering the physical world that increasingly characterizes daily life" (p. 208).

Tracing Disneyland's lineage from carnivals, pleasure gardens, and world's fairs, Sorkin recalls the ability of theme parks to craft a fantasy of nature in which humanity encounters the sublime, but in a safe and sanitized environment. Of course, the theme park also stands in contrast to the bland modern architecture that also flowed from the international imagination sparked by world's fairs. Most intriguingly, Sorkin relates Disney to the garden cities and office parks of the 20th century: urban spaces radiating outward along boulevards of commerce. Indeed, Disney may be classified as a panorama of commodified travel: an ersatz experience of mobility resting upon a foundation of tourist trinkets and Kodak-sponsored photo-spots.

In a larger sense, Disney reflects an experience of mobility that reduces each place to a momentary node within a larger continuum, what I call 'omnitopia.' Sorkin writes: "In this new city, the idea of distinct places is dispersed into a sea of universal placelessness as everyplace becomes destination and any destination can be anyplace" (p. 217). The person who inhabits this locale? The nomadic consumer. Ideally, this notion will remind you of previous classroom discussions about the nature of shopping malls and other themed environments.

Ultimately, Disneyland - a world of people movers and manufactured lawns - reflects a subtle ideology of order, despite its playful facade, communicated visually through anthropomorphic mice and other cartoon characters. This same ideology emerges also through airports and planned communities, so much so that these sites all reflect a notion of "disneyfication": perpetual movement, perpetual observation, perpetual commerce. This experience of creative geography, of editable space, constructing a fascinating paradox: "Disney invokes an urbanism without producing a city. Rather, it produces a kind of aura-stripped hypercity, a city with billions of citizens (all who would consume) but no residents" (p. 231).

[Return]