Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378

Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu

Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda

|

Dr. Andrew Wood Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378 Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda |

Reading:

Hales, P.B. (1984). Silver cities: The photography of American urbanism, 1839-1915. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

| Note: These comments are not designed to "summarize" the reading. Rather, they are available to highlight key ideas that will emerge in our classroom discussion. As always, it's best to read the original text to gain full value from the course. |

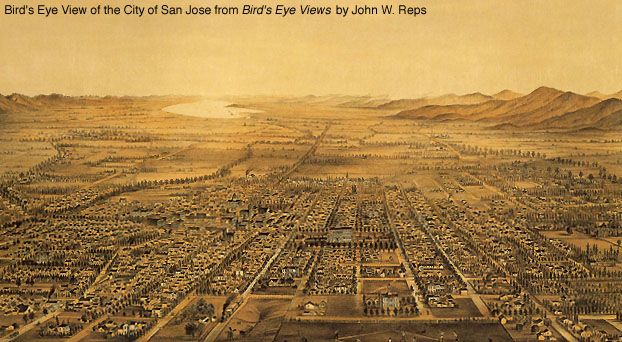

How would you create a series of images that depict the complicated reality of San Jose? What images would you choose? Which would you leave out? How would you choose? In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, one approach toward this question lay in certain forms of panorama. The study of panoramas demands our attention because they provide an under-theorized component of institutional gaze analysis. Hales begins with an analysis of the taxonomy and stylistic conventions of Gilded Age photography. His primary thesis argues that photography of the period served to affirm Victorian values and notions of power through the invocation of grand style.

Referring to the Chicago Art Portfolio, Hales writes, "In this Algeresque urban world, the photographs and photographers played out their role . . . that of ordering, civilizing, and giving sense to an urban mythos" (p. 70). Wealthy boulevards become axes for understanding the city. Slums become defined as "exotic." In many ways, the evocation of a grand style of photography emerged from a larger movement in American public life, the City Beautiful Movement: a belief in architecture as a grand unification of design, sanitation, and civilization. Predictably, the Movement found roots in the World's Fairs of the era. But it also drew from a Victorian celebration of scientific expertise and large scale planning. Here, one must recall how the photographs of the grand urban style were organized according to taxonomies: varied lists and collections of ideas that did more than orient how one might "see" a city. They formed a Foucauldian discourse of what might be seen at all.

Initially, this discourse emerged from "bird's eye" lithographs. These mass-reproduced drawn images provided a chance for the boosters of small towns and large cities to vie for commerce and recognition. Most popular after the Civil War, these images competed against photographs, a battle they soon lost. Photographers promised grand glimpses of American towns in their so-called balloon views, overhead perspectives that crafted a sense of order from chaos. Order could also be found in panoramas, vast vistas placed within one coherent scene, very much like the "bird's eye views" of lithographs. While these balloon views and panoramic photographs possessed the power of verisimilitude, they suffered too. The lithographic artist had much more freedom to narrate the myths of a town through exaggeration. The photographer could hardly ignore the inexorable realities of natural obstructions and physical distance.

In either case, the construction of a grid and perspective, the axes through which one might make sense of the scene, remained dependent upon the technologies and vantage points available. Recalling Hales' example of Denver-as-railroad-center, each photograph could be analyzed not only for what is seen, but for how that site reflects practical, economic, and political choices. Multi-plate panoramas offered one other way to capture a certain reality of urban life by piecing together several images into an (ideally) seamless whole. A image that could not be experienced from any single vantage point; one that evoked the illusion of movement as a person rotates to view a city from 360 degrees. Again, however, the cultural fiction of panoramic photography arises. The position from whence one starts (such as a mansion atop California Street Hill in the San Francisco example) determines what features and values the image privileges. The age of the urban panorama ended when cities grew too large to be enclosed by a frame, even a multi-plate frame. Attempts to capture the violence and destruction of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake represent the last gasp of the Victorian era panoramic grand photograph.

Panoramas gained much of their power from the relative ease with which they could be produced, bought, and sold. With their passing, wide-angle street views became a popular replacement. These images sought to emphasize smaller portions of the urban environment, showcasing the symbols of civilization and commerce - opera houses, train stations, post offices, hotels, and the like - in dignified, awe-inspiring perspectives. Here the buildings become symbols while people become obstacles to the aesthetic pleasure of looking. As such, human-scale interaction became a problem to be edited out of the composition of urban images. Similarly, these images provided a means to articulate the relationship between the built environment and nature, frequently employing the organic world as a site of contrast against the power of humankind.