Emphasis on the Home

The Importance of Mobile Home Communities in Silicon Valley

Jordan Weinberg & Gordon Douglas (2023)

Prepared with the support of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation.

I. Mobile Homes: An Overlooked Source of Affordable Housing

In the midst of a regional housing affordability crisis, housing need in the San Francisco Bay Area is typically (and appropriately) seen through a lens of production1,2 and further, as existing within a limited, binary typology of single or multi-family development. This framing is a rational response to the housing shortage – locally, regionally, and statewide, housing supply and production lag far behind need. Critical to meeting this need is increasing density.3 This is where a binary between single- and multi-family housing takes shape, in which single-family housing is seen to represent a dysfunctional past as an exclusionary and inefficient housing type and land use and dense, multi-family housing as the only hope for the future.4,5

This binary excludes a wider array of ideas and alternative housing types. Among other limitations, it makes no place for one of the largest unrecognized sources of affordable housing in the Bay Area: mobile home parks (MHPs). Interestingly, even active attempts to recognize and promote the importance of things like “Missing Middle” housing often still dismiss mobile and manufactured homes. For instance, in the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) inventory report on the Bay Area’s existing missing middle housing stock, a comprehensive breakdown of housing units across type and county from single-family to 20+ unit apartment buildings, mobile homes are categorized only as “other housing,” alongside “…RVs, boats, etc.”6

The lack of attention to MHPs within the Bay Area affordable housing conversation (and academic scholarship)7 may have many causes: the stigmatization of MHPs, “trailer parks,” and their residents8; the fact that MHP supply is no longer increasing in the Bay Area9; or simply ignorance of the region’s longstanding history of MHPs, which dates to the thousands of spaces created in federally-sponsored sites to address wartime housing need in the 1940s.10 Yet the Bay Area’s largest city, San José, is home to the greatest number of mobile home parks of any city in California.11 In this unlikely juxtaposition, we see in Silicon Valley – by some measures the wealthiest metropolitan area in the United States12 – a significant presence of a housing type often associated with a distinct lack of wealth and urban niceties.

This report aims to put mobile homes and RVs, their residents and owners, and the communities they form into focus. The goal is not only to raise awareness of their oft-forgotten existence in the Bay Area, but to explore their value as naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH), call attention to the precarious tenure arrangements in many MHPs that today threaten their long-term persistence, and advocate for policies to preserve and protect them.

Silicon Valley MHPs as Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing

As a housing type, MHPs do not fall as neatly into the “owner- or renter-occupied” dichotomy as do single- and multi-family housing. Mobile home and RV ownership differs significantly from traditional owner-occupied site-built homes, where property ownership typically means that of both land and the housing built on top of it. Instead, nearly all mobile home and RV owners in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties lease the lots on which their homes sit from a park owner. In Silicon Valley, park owners are generally for-profit management companies, although some are individually- or family-owned. Residents, meanwhile, are predominately low-income. And without land ownership, mobile homes and RVs fall in the category of “personal” or “chattel” property, along with possessions like cars or boat). This makes MHP residences difficult to categorize in the affordable housing context.

The term NOAH, or naturally occurring affordable housing, generally refers to “small-a” affordable rental housing: unsubsidized, affordable due to market conditions such as building age, condition, or location that make it relatively less desirable. Yet affordability measurements differ, as do their applications. The most widely-adopted definition comes from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which defines affordability as housing that costs less than 30% of household income.13 However, this definition is often applied only to multifamily housing due to data limitations on smaller housing types.14

Positioning MHPs in a NOAH framework is also made difficult by the lack of available MHP-specific data. For example, Datacomp/JLT, an authoritative source of market data for manufactured home communities (mobile homes only, RVs excluded), does not include San Mateo County as part of its West Coast county-level reporting.15 Datacomp/JLT market reports do include Santa Clara County, with data bifurcated by residential restriction: “All Ages” or “55+”.16 Still, in Santa Clara County, lot rents are affordable (defined as rent as < 30% of income) to very-low income residents (defined as 50% of AMI). This helps to contextualize the affordability of mobile home-only lot rents as compared to median income.

Analysis is further complicated by a lack of comprehensive data on occupancy type (RV versus mobile home) and thus of additional costs beyond lot rent, such as mortgages. Still, the available data begin to tell a story of lot rents broadly affordable to a wide spectrum of household incomes, and mortgage payments that are likely to fall far below those of nearby single-family homes. Because the California Association of Realtors (CAR) excludes mobile home sales from its data on sale prices for single-family homes, we used an MLSListings database of mobile home sales for the same period to compare median sale price in San Mateo and Santa Clara counties. We then estimated mortgage payments on four hypothetical homebuying scenarios (not including property taxes or insurance), showing a wide gap in monthly payments based on differences in sale price using rate terms provided by 21st Mortgage Corporation and Rocket Mortgage (the nation’s leading mobile home mortgage and traditional mortgage lenders, respectively.17,18 While actual numbers will of course fluctuate due to individual and market conditions, we can form a baseline assumption that monthly mortgage payments on mobile homes are likely markedly lower than single-family homes. (Our evaluation of estimated mortgage payments is detailed in the Appendices).

The sheer scope of mobile homes in Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties is dizzying. In this two-county region there are 127 MHPs, comprising 22,401 mobile home spaces and RV lots.19 San José MHPs alone total 10,716 mobile home spaces and RV lots, which some 35,000 of the city’s residents call home.20 Five of the ten largest MHPs in California are found in Santa Clara County, including the two largest, Casa de Amigos and Plaza Del Rey, both in Sunnyvale. These two parks, which border one another, represent 1,723 contiguous units of mobile homes in one of the most expensive places to live in America.

These numbers paint a surprising picture of Silicon Valley, a highly-urbanized region and one where housing stock is more commonly conceived of in simple single- or multi-family terms. And this high-level data on total mobile home spaces and RV lots only begins to tell the story. For a more complete picture of these essential places, this study combines both quantitative and qualitative analysis of MHPs in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties, connecting the raw numbers to locations, demographics, and community character, presented in this written report and an interactive online map. The goal is to improve public understanding of the value of our region’s mobile home residences both as vital components of the housing supply and as diverse, lived communities as worthy of preservation as any other.

2. Mapping Silicon Valley’s Mobile Home Parks

Mapping the locations and community data for MHPs in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties was a multi-step process, combining information from several sources into a data-rich map using ESRI ArcGIS software (a detailed description of the mapping methodology is provided in the Appendices). The Department of Housing and Community Development’s Codes and Standards Online Services (C&S OS) Mobilehome/RV Parks database provides a comprehensive starting point for mapping physical locations (street address) with park type (mobile home only, RV only, or mixed) and some other park-specific information. This allowed us to create a unique base map showing all mobile home parks in the two county region.

Interactive Map of Mobile Home Parks in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties

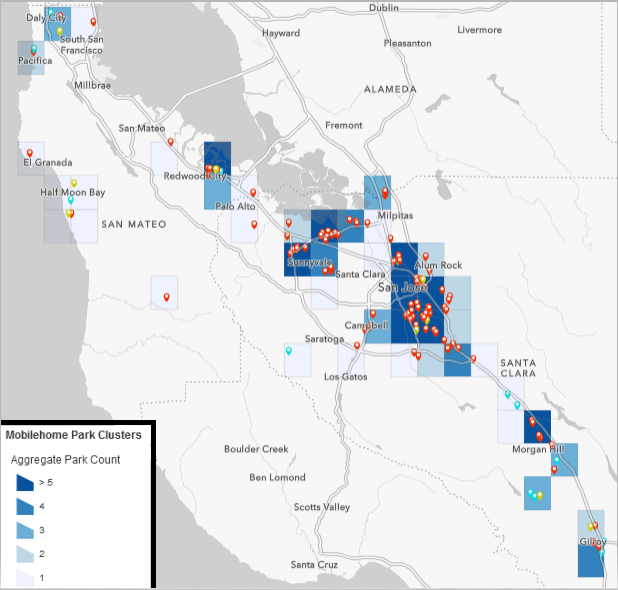

MHPs span a significant geographic extent, from Daly City to Gilroy, and from bay to ocean waters. Spatially however, MHPs are concentrated in a few small areas. These include Redwood City, sandwiched between bay salt ponds and US 101; alongside the SR 237 and SR 85 intersection in overlapping Sunnyvale and Mountain View, and again near northernmost Sunnyvale; and in Morgan Hill’s northernmost Madrone neighborhood. The next map below displays aggregate clusters of the 127 MHPs throughout the two counties.

Mobile Home Park Clusters in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties

The largest cluster, and group of clusters, is found in San José, especially along Monterey Road, one of the city’s major corridors. There are 28 MHPs in a less than 6-square mile area within no more than 1 1⁄4 miles of Monterey Road. To put this in perspective, 22% of all MHPs in Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties are grouped around Monterey Road in South San José, in an area representing just 0.03% of the region’s total land area. (15 more MHPs are found further south along Monterey Road in the 20 miles between San José and Gilroy.)

Despite this significant clustering, MHPs are also found across a wide diversity of land uses - bordering residential (single- and multi-family), commercial, industrial, and green space designations, sometimes simultaneously. The location of MHPs appears much less determined by any present-day notions of isolation and more by historical patterns of MHP development along transportation and industrial corridors.21 In this sense, the location of MHPs might be better understood as following the same patterns that drove other postwar suburban development, albeit at a much smaller scale. MHPs should be seen as part and parcel of the Silicon Valley landscape, rather than othered or ghettoized.

3. Mobile Home Residents

Having built an understanding of the spatial patterns of MHPs in Silicon Valley, this section focuses on their community-level demographic attributes. To add demographic information, which is missing from the state’s C&S OS database, we needed to layer data from the 2020 U.S. Census and the 2017-2021 American Community Survey into our map. Although data are not available at a unit or park level, short of conducting door-to-door surveys, we were able to isolate Block Group-level demographic data for the 10 Census Block Groups in the two counties in which 75% or more of all housing units are mobile homes, RVs, boats, or vans. (Please see the Appendices for details on the data mapping methods.) The 10 Block Groups each contain between 1 and 6 MHPs, for a total of 20 MHPs or just under 16% of total MHPs in the two county region. (Detailed data from these select Block Groups and corresponding data at the county-level are displayed in Tables 3 and 3 in the Appendices.) This section focuses on these 10 Block Groups where we are confident that the data best represent MHP communities.

In contrast to the dominant stereotype associating whiteness and MHPs,22 only one of the 10 Block Groups has a white majority or plurality (our Block Group 1: Census Tract 5048.07 in Sunnyvale). Instead, communities of color are actually overrepresented in the remaining 9 Block Groups compared to county averages, with 5 of the Block Groups majority/plurality Latinx and 4 majority/plurality Asian. White populations are actually below county averages in 8 of the 10 Block Groups, including all Block Groups in San Mateo County. All of the select Block Groups reflect below-median household income, yet all also show ownership rates (and non-white ownership rates in all but Block Group 1) that far exceed county averages.

Consider for example our Block Group 2, Census Tract 5043 in San José, the leader amongst all select Block Groups in non-white homeownership rate. Block Group 2 is 69% Asian, 21% Hispanic or Latino, 6% white, less than 1% African American, and 3% all other races. With a median household income under $83,000, this Block Group would be classified as Very Low Income according to State Income Limits as set by HCD. Of the 144 Block Groups in Santa Clara County that fall within the Very Low Income category ($53,200 - $89,200), Block Group 2 ranks measurably higher than average in both rates of total homeownership (69.3% vs. 37.6%) and non-white homeownership (93.2% vs. 70.4%).

The relationship between low-income communities of color and homeownership rates in MHPs is a vital one. These findings suggest that MHPs offer a viable path to homeownership for low-income communities of color, one with a far lower financial barrier to entry. However, as residents are not landowners in all but two parks in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties, their homes are titled as personal rather than real property, which has a considerable effect on financing sources. Curiously, both chattel (personal property) and manufactured housing mortgage applications (real property) are denied at national rates substantially higher than site-built mortgage applications.23 Further research would do well to explore the advantages and disadvantages that low-income communities of color in Silicon Valley face in financing the purchase of their mobile homes and how this compares to the national data.

As discussed above, we calculated a simple analysis of debt service on four sample mortgage scenarios with an 80% LTV ratio to underscore the affordability status of mobile home ownership. Affordability may play an important role in the ability of residents in the select Block Groups to maintain higher-than-county-average ownership rates while at the same time also receiving non-employment income at higher-than-county average. In other words, even though rates of homeownership are high, MHP residents are susceptible to increases in lot rent (when not landowners), and rent increases may be felt more strongly by households with a greater reliance on non-employment income (i.e. fixed-income status). This provides additional impetus for MHP preservation and resident protection policies.

4. Place and Community

A final layer of data needed to understand the significance of MHPs in Silicon Valley was collected through qualitative fieldwork. In order to document and analyze local character and community within MHPs, we selected a sample of 20 parks to visit, photograph, and get to know. These included 10 parks randomly selected from the 127 total MHPs in the two counties, as well as the five largest mobile home-only parks in the region, the largest mixed RV and mobile home park, the largest RV-only park, a second large RV-only park, and the two parks that are resident-owned (both of which are also age-restricted 55+ communities). Researchers photographed shared community facilities as well as individual homes and streets, chatting with residents and visiting park offices when possible.

Visits to these parks between April and July of 2023 showed vibrant, well-established communities. Most (15 out of 20) had community centers with shared event spaces (sometimes more than one) alongside a park office, often smartly decorated. Community facilities also often include parklike grounds and landscaped paths, swimming pools, and tennis courts. Especially in parks composed entirely of larger double-wides and other manufactured (but not literally mobile) homes, units generally are fully fixed in place, surrounded by sitting porches and landscaped gardens; some are nearly indistinguishable aesthetically from an upscale suburban subdivision. The two RV-only parks had fewer such signs of permanence, but many units still had potted plants and porch-like outdoor seating areas; both also had community centers, shared walkways, and other signs of neighborhood life, and one had a pool and a small shop selling art and crafts made by residents.

Among the 15 parks we were able to confirm founding dates for, 12 have been around since at least the 1970s (even if several have changed hands or reincorporated more recently). We learned the longest-term residents of some parks had lived in their community for decades, and this was as true in the relatively “simplest” RV parks as in more affluent communities of elegant double-wides and manufactured homes. We frequently noted signs advertising parkwide events for residents, and many clubhouses featured things like communal book exchange libraries (even a small park with limited amenities had a book exchange in its laundry room).

MHPs have long dealt with significant stigmatization and negative stereotyping.24 Our research makes clear that the cultural preconceptions do not hold up: the places we visited are pleasant, safe communities with diverse, long-term residents. Many parks include beautiful well-cared for homes and grounds and appealing amenities. In short, Silicon Valley’s MHPs are neighborhoods like any other, enviable places to live by most standards, especially in a region with such limited and high-cost housing supply. The main ways they differ – being generally denser and more affordable than traditional single-family subdivisions – are also quite desirable from an urban planning perspective, except for one other major difference: their unique property and tenure arrangements, which complicate homeownership and make residents especially vulnerable to displacement. The task for affordable housing advocates and policymakers must be to find ways to preserve MHPs and improve residents’ abilities to remain.

5. Preserving Mobile Home Housing

Mobile home parks present a unique paradox in affordable housing: NOAH with some elements and possibilities of property ownership. Unfortunately, in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties, less than 2% of mobile home owners lay claim to the land underneath them.25 This bifurcated ownership structure, or tenure arrangement, which separates owners of the property and the land, has placed MHPs in investors’ crosshairs. The changing face of MHP ownership has been called “corporate,”26 “big pocketed,”27 “institutional,”28 and touted as an investment that “offer[s] exceptional upside opportunities.”29 MHPs in San Mateo and Santa Clara County do present tantalizing opportunities not only as rental properties, but as potential redevelopment sites on some of the most valuable real estate in the United States.30

The 800-unit Plaza Del Rey community in Sunnyvale, for instance, was purchased by the Carlyle Group for $150 million in 2015 and sold just four years later for $237 million to Hometown America Communities, a Chicago-based company that owns MHPs nationwide.31 On the development side, the Winchester Ranch Mobilehome Park was purchased by Pulte Homes for $50 million in 2015 and two of the country’s biggest homebuilders, PulteGroup and Hanover Company, are currently constructing 687 units of single- and multi-family housing there.32

Cities in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties have enacted a patchwork of policies in recent years to strengthen resident protections. Rent stabilization ordinances, land use designations, and conversion restrictions work in concert to help ease rent burden and stave off redevelopment. Yet all are absent of long-term affordability preservation or any structural change to MHP tenure arrangement and property designation, meaning mobile home owners still face limitations ranging from financing to value appreciation over time. The following sections detail policies in place, and those recommended, to address these issues and more.

Mobilehome Rent Stabilization

A number of rent control or rent stabilization policy models exist in the San Francisco Bay Area, often capping year-over-year rent increases at the higher of either a fixed percentage increase (e.g. 5%) or some percentage of the rise of inflation (e.g. 75% of 12-month Consumer Price Index), sometimes with the option of a capital or operating expense pass-through with the approval of a city council or other governing body. While most of the MHPs in Silicon Valley are protected by such ordinances in their respective jurisdictions, an obvious first step is enacting them where there are none, such as Redwood City. Even where protections are in place, gaps still exist. For example, a measured rent stabilization ordinance might limit extreme rent increases of the type often meant to discourage residents from renewing their lease, but even modest rent hikes over time place an increasingly difficult burden on the low- and fixed-income residents that comprise many MHPs in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties and who already face some of the nation’s highest rents relative to their housing type.33

Cities would be wise to move away from an “MOU-model” such as that in Sunnyvale, where a 20-year Memorandum of Understanding between the city and MHP owners regulates rent increases for MHP residents.34 Nearby Mountain View drafted but then abandoned a similar policy, recognizing that with no requirement for MHP owners to sign the agreement this did little to assuage rent hike fears.35

Aside from increased income, part of the rationale for rent increases is to compensate for increased operating expenses or capital improvement costs. In some cities’ policies, however, rent increases up to the maximum annual percentage are considered sufficient to account for such costs incurred by the park owner.36 The relationship between rent increases on one hand, and sustained MHP operation and capital improvements on the other, must be further explored to better understand how MHP owners respond to rent increases and whether scheduled maintenance and capital projects are completed or deferred.

MHP-Specific Land Use Designation

In Silicon Valley, where real estate prices boom (and boom fast), speculative interest might cause an abrupt shock to the MHP status quo. Park owners might then envision increased profit from altering the land use – for example, transitioning from mobile home parks to single- and multi-family residential development, as was the case at San José’s Winchester Ranch Mobilehome Park.37 Building off of rent stabilization, which may help to discourage the view of MHPs as investment vehicles in and of themselves, cities might adopt MHP-specific land use designations through some combination of a General Plan amendments and conditional use permits to ward off speculation for the land underneath and future use of the land for other purposes.

Such a policy should soon exist in San José, where the city is undergoing a General Plan amendment process with the expressed goal of “reducing conversion risk of those MHPs sitting on parcels with economically lucrative land use designations.”38 The genesis of this policy comes from a unanimously approved decision by the City Council in March 2020 – spurred in large part by community organizing – which was set to place all of the city’s 58 MHPs under a mobile home-only land use designation to prevent redevelopment risk. Unfortunately the process has been slow, and funding uneven.39 When MHP protections first made their way to the 2022-2023 budget, the City Council dramatically scaled back the scope for expanded land use protections to just 5 MHPs “at the greatest risk of redevelopment for other uses,” before increasing this number to 13 in late 2022.40 The 2023-2024 Proposed Budget adds additional one-time funding of $240,000 to extend land use protections to the remaining 43 MHPs. Three and a half years and now $375,000 later, since the policy was initially approved, the focus now is on San José’s Housing Element, which targeted January 2024 for the revised land use designations of the 13 at-risk MHPs (approved by City Council in December 2023), and June 2024 for the remainder.41

The slow movement on MHP-specific land use designation in San José underscores broader challenges. For one thing, if a city with 35,000 MHP residents – over three percent of the city’s entire population and the largest such community in the state42 – is still unwilling or unable to advance MHP preservation efforts, what hope is there for analogous efforts elsewhere in Silicon Valley, where mobile home communities may be even more overlooked? More fundamentally, land use designations defined to permit only mobile homes may work to prevent redevelopment but do nothing to reform tenure arrangements or property designations. The MHP is preserved, yet residents are no closer to real property ownership, whether as individuals or cooperatives. And so while a mobile home park holds and gains value to potential lessors as real property, a mobile home itself often decreases in value as personal property, in much the same way as other depreciating assets like cars or boats.

Conversion Ordinances and Closure Moratoriums

Even with an MHP-specific land use designation, conversion to another use (e.g. single- or multi-family housing) is not prohibited, only slowed or discouraged by the additional hurdles of processes like city council approval, General Plan amendment, or conditional use permit. In this way, conversion ordinances essentially codify the process. The best hope for MHP residents in these cases is to codify more equitable conversion processes that mitigate displacement. San José’s Mobilehome Conversion Ordinance demonstrates an array of options for doing so, including relocation of the mobile home itself, reimbursement of moving expenses, fair market rent subsidies, payment of the difference in lot rents, or purchase of the mobile home at its appraised value.43 The ordinance could serve as a model.

Of course, concerns may still arise over the amounts of compensation. For instance, a resident profiled in the aftermath of the Winchester Mobile Home Park development agreement received a buyout over six times what she paid in 1977, but adjusted for inflation, the value of that buyout shrinks considerably.44 While compensation might be fair market value, mobile homes accrue significantly less appreciation than site-built homes. This same former resident may then face difficulties re-entering the local housing market with that amount of money as a renter or buyer, potentially resulting in the same displacement that a conversion ordinance hopes to avoid. Thankfully, in the case of Winchester Mobile Home Park, the agreement also provided most residents with interim housing during construction and replacement housing in the new development upon completion. Such direct housing assistance might also be made a required standard of conversion ordinances.

A related concern may be that conversion can cause the fracturing of an entire community, even with replacement housing or compensated relocation, as displaced MHP residents could experience the loss of their neighborhood and the cultural, economic, and social ties that bind them. Given the intensified speculation on mobile home parks and the scale at which an entire MHP would be sold or converted, this is an existential threat nonexistent to many other housing types. The diverse residents of MHPs are as valuable members of our cities as any others, and their communities are as vital as any other neighborhoods. It might then be wise for cities reviewing or enacting conversion ordinances to view the ultimate protection as a moratorium on conversions (and closures), rather than simply compensation or replacement housing in the event of conversion. This would advance protections even further than that of MHP-specific land use designations which, if subject to council approval, are dependent on the shifting winds of political support. There is some local precedent for this action, as San José placed a temporary moratorium on conversions and closures for over 18 months while developing its MHP zoning ordinance.45

Towards Resident Ownership

As discussed, the most common tenure arrangement in MHPs finds the mobile home owner paying a ground lease, owning their manufactured home but not the land it sits on, with the home thus being titled as personal property rather than real estate. We have seen the implications of this property arrangement across the policy challenges described here. It has implications on everything from monthly expenses to lending, asset-building, and appraisal – the last of which has knock-on effects on both tax and resale value as well.46 Indeed, the property designation of mobile homes has been a source of considerable debate since the postwar boom in MHPs across the country.47 Interest groups, financial institutions, and public agencies have produced a bevy of materials providing technical assistance and best practices on titling mobile homes as real property,48 yet without ownership of land, residents continue to face considerable difficulty if not an outright inability to title their mobile home or RV as real property.

The obvious solution is resident ownership of the MHP itself. Such a place – a mobile home park where the residents own both their homes and land – is often referred to as a “resident-owned community” or ROC. Although ROCs represent just two percent of mobilehome parks nationwide, or around 1,000 parks in total, nearly a quarter of America’s ROCs are found in California.49 Yet in Silicon Valley, only two ROCs exist: Paseo de Palomas Mobile Home Park in Campbell and Woodland Residents Inc. (Woodland Estates) in Morgan Hill.

Some cities, including San José, have established processes to streamline MHP conversion to resident ownership. These policies expand on codified conversion processes as outlined above. San José’s “Mobilehome Park Conversions to Resident Ownership or to Any Other Use” ordinance outlines the requirements and procedures of this process as it relates to land use conversion or the intent to transfer ownership to a ROC (although there are no ROCs in San José). Common interest ownership by a ROC, or Designated Resident Organization as they are referred to in San José’s ordinance, must represent at least 10% of spaces in the park and must provide written notice of intent to purchase within 60 days of a notice of intent to convert being issues by the current park owner.50

Conversion to resident ownership requires access to considerable financing, made more difficult by the large price tag on land in Silicon Valley. In a list of five recent transactions we reviewed across Santa Clara County, MHPs fetched an average of $75.87M per park, and $263,600 per space. Often, ROCs take the form of a limited-equity cooperative. Rather than ownership of individual lots, residents typically own shares in the entity that owns the MHP. At the national scale, this limited-equity cooperative ROC model is almost synonymous with ROC USA, a non-profit social venture that works with a group of regional affiliates and ROC USA Capital, a CDFI lending subsidiary to provide technical assistance and advance resident-ownership of MHPs nationwide.51 Although ROC USA only requires that a simple majority of 51% of residents buy into the limited-equity cooperative, in practice that number is usually greater than 75% or more.52 This thus requires considerable efforts on the part of MHP residents looking to form a ROC.

The ROC is perhaps the tool with the greatest potential to preserve MHPs in perpetuity, as it provides long-term stability by removing the threat of conversion, attenuates rent increases or at the very least makes changes in rent at the discretion of the resident cooperative, and enables residents to determine their own capital improvement needs and set their own maintenance fees. Although there are only two ROCs in Silicon Valley, residents at Palo Mobile Estates in East Palo Alto are attempting to establish the third. The financing gap, around 90% of the $20M it will take to close on the property, underscores the challenges MHP residents face in accessing enough capital to purchase their parks.53 Cities should explore the extent to which they can assist in providing grant funding, forgivable loans, bonds and other financing tools that support an outright purchase or help lower the total equity MHP residents must raise or borrow.

In nearby Santa Cruz County, nearly two dozen MHPs are resident owned.54 One, Alimur Park, was purchased by its residents in 2015, the same year the Winchester Ranch Mobile Home Park was purchased for redevelopment. With 147 spaces, Alimur Park presents a great case study for both MHP residents and Silicon Valley cities to learn best practices in resident organizing and securing financing. The purchase price of $11M (not including related costs and reserve accounts) is comparable to present-day park purchase prices and again reflects some of the challenges MHP residents in Silicon Valley face in contending with one of the most expensive real estate markets in the world.55 The $20M price tag on the Palo Mobile Estates in East Palo Alto is not only higher in total, but over twice as expensive per lot. Thus, city, county or state intervention in the form of access to capital or technical assistance will be of paramount importance to supporting resident ownership here. One way or the other, addressing the precarious tenure relationship of MHP residents is an essential concern for the sustainability of this important housing source in Silicon Valley.

6. Conclusion

Based on the widespread indifference to or exclusion of MHPs from the present housing discourse, prevailing sentiment might be that Silicon Valley does not have many, or any, mobile homes. The data tell us otherwise. MHPs are widespread throughout the region, highlighted by major concentrations in certain areas, providing a large amount of housing. They are diverse communities that offer a unique combination of naturally occurring affordable housing with some possibility of property ownership, including far higher rates of home ownership among people of color than in other types of housing. And they are pleasant, appealing, longstanding, tight-knit places as established and important as any other neighborhoods in our region. Understanding MHPs requires recognition of their rightful place in the affordable housing discussion, while at the same time acknowledging that their unique tenure arrangements demand targeted policies of preservation that are distinct from more common housing types.

Further investigation of the links between MHPs and affordable housing, and more specifically NOAH, requires a re-shaping and expansion of how we define NOAH so that it may better include mobile homes. Future research on NOAH must work to create MHP-specific affordability criteria to better understand just exactly how affordable MHPs are and how we can apply a discussion of affordability to the MHP tenure arrangement that better serves preservation and protection efforts. The affordable housing conversation does not end with MHPs, but as the nation’s largest source of unsubsidized affordable housing it is as important a place as any to start.56

References

1. Plan Bay Area. Plan Bay Area 2040 Final Plan. Accessed on March 17, 2023.

2. Karlinsky, Sarah & Kristy Wang. 2021. “What It Will Really Take to Create an Affordable Bay Area [pdf].” SPUR. Accessed on March 17, 2023.

3. Taylor, Mac. 2015. “California’s High Housing Costs Causes and Consequences [pdf].” Legislative Analyst’s Office. Accessed on March 17, 2023.

4. Menendian, Stephen, Samir Gambhir, Karina French & Arthur Gailes. 2020. “Single-Family Zoning in the San Francisco Bay Area.” UC Berkeley Othering & Belonging Institute. Accessed on March 17, 2023.

5. Varian, Ethan. 2022. “Does the Bay Area have enough water to build housing during the California drought?” Mercury News. Accessed on March 17, 2023.

6. ECONorthwest. 2021. “The Bay Area’s Middle Housing Market [pdf].” Report prepared for: Association of Bay Area Governments. Accessed on March 17, 2023.

7. Lamb, Zachary & Linda Shi, Jason Spicer. 2023. “Why Do Planners Overlook Manufactured Housing and Resident-Owned Communities as Sources of Affordable Housing and Climate Transformation?” Journal of the American Planning Association: 89 (1).

8. Kusenbach, Margarethe. 2009. “Salvaging Decency: Mobile Home Residents’ Strategies of Managing the Stigma of ‘Trailer’ Living.” Qualitative Sociology: 32.

9. Association of Bay Area Governments and Metropolitan Transportation Commission. 2021. “Housing Needs Data Report: San Jose.” Accessed on March 17, 2023.

10. Foster Jr., Richard H. 1980. “Wartime Trailer Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area.” Geographical Review: 70 (3).

11. Pham, Loan-Anh. 2022. “San Jose’s largest mobile home park gets new name, management.” San Jose Spotlight. Accessed on February 20, 2023.

12. In per capita income, the San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara metropolitan statistical area ranks first, while San Francisco-Oakland-Berkeley, inclusive of San Mateo County, ranks fourth. See U.S. Department of Commerce. 2023. “Regional Data GDP and Personal Income.” Accessed on November 05, 2023.

13. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). 2014. “Rental Burdens: Rethinking Affordability Measures.” Accessed on July 29, 2023.

14. Alvarez-Nissen, Matt, Danielle Mazzella, Anthony Vega & Traci Mysliwiec. 2023.“Naturally-Occurring Affordable Homes At Risk [pdf].” California Housing Partnership Corporation. Accessed on July 29, 2023.

15. Freddie Mac. 2018. “Duty to Serve Underserved Markets Plan For 2018-2020 [pdf].” Accessed on July 29, 2023.

16. Revere, Patrick. 2023. “Manufactured Housing Industry Trends & Statistics.” MH Insider. May 22, 2023. Accessed July 29, 2023.

17. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). 2021. “Manufacture Housing Finance: New Insights from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act [pdf].” Accessed August 1, 2023.

18. Fontinelle, Amy. 2023. “10 Largest Mortgage Lenders in the U.S.” Forbes. July 31, 2023.

19. California Department of Housing and Community Development Codes and Standards Online Services (C&S OS). N.d. Web search for Mobilehome/RV Parks. Accessed on March 17, 2023.

20. Hansen, Louis. 2022. “San Jose’s largest mobile home park safe, for now.” The Mercury News. Accessed on July 29, 2023.

21. Foster Jr., Richard H. 1980., “Wartime Trailer Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area.” Geographical Review: 70 (3).

22. Sisson, Patrick. 2017. “Mobile-home parks represent changing face of affordable housing challenge.” Curbed.

23. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). 2021. “Manufacture Housing Finance: New Insights from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act [pdf].” Accessed August 1, 2023.

24. Kusenbach, M. 2009, op. cit.; Saatcioglu, Bige & Julie L. Ozanne. 2013. “Moral Habitus and Status Negotiation in a Marginalized Working-Class Neighborhood.” Journal of Consumer Research: 40 (4).

25. MHPHOA. 2022. “California Mobile Home Parks.” MHPHOA. Accessed February 05, 2023.

26. Raisinghani, Vishesh. 2022. “Corporate landlords are gobbling up mobile home parks and rapidly driving up rents – here’s why the space is so attractive to them.” Moneywise. August 30, 2022.

27. Casey, Michael and Carolyn Thompson. 2022. “Rents spike as large corporate investors buy mobile home parks.” Los Angeles Times. July 25, 2022.

28. Kasakove, Sophie. 2022. “Investors Are Buying Mobile Home Parks. Residents Are Paying a Price.” The New York Times. March 27, 2022.

29. Keel, Andrew. 2022. “The Future of Mobile Home Park Investing: Three Big Names.” Forbes. April 6, 2022.

30. Echeverria, Daniella. 2021. “See how much more expensive Bay Area real estate is compared to other cities.” San Francisco Chronicle. July 9, 2021.

31. Avalos, George. 2019. “Big Sunnyvale mobile home park is bought by Chicago investors.” The Mercury News. August 30, 2019.

32. City of San Jose Planning Commission. 2019. Memorandum. Accessed February 05, 2023.

33. Revere, Patrick. 2023. “Manufactured Housing Industry Trends & Statistics.” MH Insider. May 22, 2023. Accessed July 29, 2023.

34. City of Sunnyvale. N.d. “Sunnyvale Mobile Home Park Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) Frequently Asked Questions & Information Page.” Accessed August 05, 2023.

35. City of Mountain View. 2021. “Introduction of an Ordinance Enacting Mobile Home Rent Stabilization.” Accessed on August 05, 2023.

36. City of San Jose. N.d. “17.22.450 – Rent increases allowable without review.” Accessed May 14, 2022.

37. Wipf, Carly. 2021. “Seniors empty San Jose mobilehome park after years of debate.” San Jose Spotlight. March 11, 2021.

38. City of San Jose. 2022. “2022-2023 Adopted Operating Budget.” Accessed February 05, 2023.

39. Nguyen, Tran. 2022. “Little progress made to protect San Jose mobile homes.” San Jose Spotlight. June 20, 2022.

40. City of San Jose. 2022. “2022-2023 Adopted Operating Budget.” Accessed February 05, 2023.

41. City of San Jose. 2023. “Housing Goals and Strategies.” Accessed August 03, 2023.

42. Jhabvala Romero, Farida. February 25, 2016. “San Jose Strengthens Protections for Mobile Home Park Residents.” KQED radio.

43. City of San Jose. N.d. “FAQ Winchester Ranch Mobilehome Park.” Accessed April 24, 2022.

44. Woudenberg, Carina. 2019. “Six years later, Winchester Ranch Mobile Home Park closure continues.” San Jose Spotlight. February 20, 2019.

45. City of San Jose. 2023. “Mobilehome Park Protection and Redesignation Project.” Accessed on August 05, 2023.

46. National Consumer Law Center. October 2014. “Titling Homes as Real Property [pdf].” Accessed February 5, 2023.

47. See Berney, Robert E. & Arlyn J. Larson. 1966. “Micro-Analysis of Mobile Home Characteristics with Implications for Tax Policy.” Land Economics: 42 (4); Bair Jr., Frederick H. 1967. “Mobile Homes. A New Challenge.” Law and Contemporary Problems: 32 (2). Mrozek, Donald Lee. 1972. “The Search for an Equitable Approach to Mobile Home Taxation.” DePaul Law Review: 21; Mason, Carl & John M. Quigley. 2007. “The Curious Institution of Mobile Home Rent Control: An Analysis of Mobile Home Parks in California.” Journal of Housing Economics: 16 (2); Al-Rousan, Tala M., Linda M. Rubenstein & Robert B. Wallace. 2015. “Disability levels and correlates among older mobile home dwellers, an NHATS analysis.” Disability and Health Journal: 8 (3).

48. California State Board of Equalization. 2001. “Assessment of Manufactured Homes and Parks [pdf].” Accessed on March 17, 2023; Fannie Mae. 2020. “Titling Requirements for Manufactured Homes.” Accessed on March 17, 2023; Freddie Mac. 2022. “Identifying the Opportunities to Expand Manufactured Housing [pdf].” Accessed on March 17, 2023.

49. Freddie Mac. 2019. “Manufactured Housing Resident-Owned Communities [pdf].” Accessed February 05, 2023.

50. City of San Jose. 2016. “Title Conversion of Mobilehome Parks to Other Uses.” Accessed February 20, 2022.

51. ROC USA. 2023. “Mission & History.” Accessed on March 17, 2023.

52. Freddie Mac. 2019. “Manufactured Housing Resident-Owned Communities [pdf].” Accessed February 05, 2023.

53. Guzman-Rodriguez, Wendy. December 30, 2022. “East Palo Alto Mobile Park Residents’ Last Shot At Ownership.” Partnership for the Bay’s Future.

54. County of Santa Cruz. 2018. “List of All Santa Cruz County Mobile and Manufactured Home Parks [pdf].” Accessed on August 05, 2023.

55. Alimur Park Homeowners Association. 2015. “Information Statement [pdf].” Accessed on August 05, 2023.

56. Sullivan, Esther. 2021. “Becoming Visible in the Public Sphere: Mobile Home Park Residents’ Political Engagement in City Council Hearings.” Qualitative Sociology: 44.